Climbing the Great Pyramid of Giza 🧗

In 2014, I visited Egypt in order to climb the Great Pyramid of Giza. Ascending pyramids isn’t without precendent: in Innocents Abroad, Mark Twain recounts how one of his guides was able to sprint to the top of the Pyramid of Khafre, descend it, jog a quarter mile to the Pyramid of Cheops and climb up and down that one in only eight minutes and forty-one seconds. My climb took significantly longer and I only climbed half as many pyramids, but I was successful nonetheless. In this blog post I’m going to tell you the story of my ascent and give you some tips for the next pyramid you climb.

The Japanese Book

Eason and I were holed up in a hotel in downtown Kiev, right next to the Maidan Nezalezhnosti, the city square that was epicenter of protests that had led to the toppling of the government a few months earlier - the Russian invasion soon followed, then the annexation of Crimea, the war in Donbass and all the killings… In the Maidan, we saw pictures of the martyrs - their portraits strung up on clotheslines and flapping in the bitter cold breeze - the faces stern, frozen forever.

Ukraine’s currency had collapsed and our US dollars went a long way: we visited the radioactive city of Chernobyl, tried every kind of food we could think of, rented a nice room… But the freezing weather kept us trapped inside, drinking lemon tea all day, chatting with the friendly hostess who served us warm biscuits, taking only short excursions outside to explore the city. At some point we decided to escape to Egypt. One of us had the idea of visiting Giza, climbing the pyramid…

We pulled out our laptops and did some research. Snow was drifting past our room’s fogged-up windows. Climbing the pyramids is illegal, we soon discovered, and people have been arrested, imprisoned, and deported for doing it. But in the past the pyramids were frequently ascended: Napoleon did it, as did Lord Byron, and probably Alexander the Great. Articles warned us that climbing was treacherous: surfaces polished smooth and slippery by the desert sand, loose rocks, crumbling footholds…

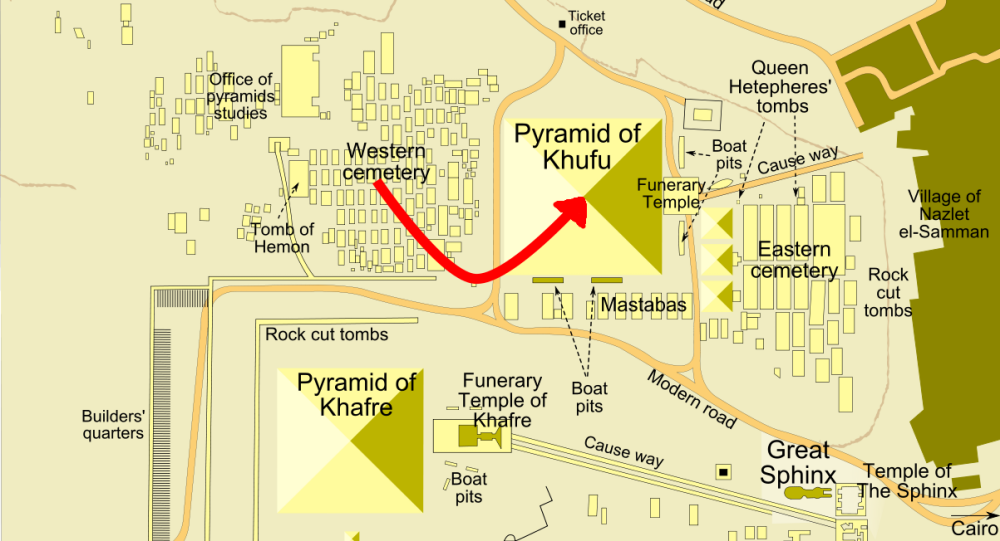

We learned that there are three large pyramids at Giza and several smaller ones: the Pyramid of Khafre still has its exterior casing stones intact near the top, giving it a frosted mountain-top appearance. The Pyramid of Menkaure is the smallest of the three. The largest is the Pyramid of Khufu - the Great Pyramid - in the northern part of the Giza plateau. That’s the one we wanted to climb.

Details were still scarce. There were suggestions of a dedicated pyramid-climbing community; hints that appeared on blog posts like climbers from Finland visit every year. Tracking down this secret brotherhood proved challenging. Climbers are often asked to pay bribes. There was the tantalizing mention of a hotel where Japanese climbers congregated. In this hotel was supposed to be a book where travelers left their stories… We decided to give it a shot.

The Riddle of the Sphinx

Q: What goes on four feet in the morning, two feet at noon, and three feet in the evening?

A: 男—赤ちゃんのように四つん這いになり、大人のように両足で歩き、老後は杖を使う

A few days later we were in Egypt. We arrived late at night and took a taxi to the city center. Cairo was chaotic, dirty. Rats were camped out on piles of garbage, completely fearless, boldly munching on litter even as we passed close by. Like Kiev, Cairo had been the scene of recent political upheaval - Tahrir Square had flooded with protesters, Mohamed Morsi was ousted as president, the constitution was suspended, tourists fled… There was a strange feeling of emptiness here, abandonment, in one of the densest cities in the world.

The city was confusing. We walked in circles until we finally found the hotel. I pressed the buzzer and was let inside. It was in one of those ancient colonial buildings, tall spiral of stairs corkscrewing upwards around the hollow interior. The remains of an elevator were smashed on the ground floor. We climbed until we reached the hotel.

The manager was friendly, still young enough to have acne. On the wall behind the reception desk was an enormous bookshelf. It stretched all the way to the other end of the room. As Eason checked in I began examining the shelves. Manga. Shelves and shelves of manga comic books. Some of it was in Arabic, but it was mostly Japanese. I asked the manager if he spoke Japanese and he said that he was still learning - it became clear that he had an obsession with Japanese cartoons.

I searched the entire bookshelf but couldn’t find what I was looking for - no journals, nothing handwritten, hardly anything except yellowing comic books. I debated asking the manager directly if there was a pyramid-climbing book, but decided against it. Instead I retreated to the room to sleep.

The private room we’d booked turned out to be less than private - the walls didn’t reach all the way to the ceiling - it felt more like a bathroom stall than a hotel room. Mosquitos poured over the divider, so I bundled myself up under all my jackets. I told Eason about my failure to find the book and he forgave me. We caught a few hours of sleep before setting out the next morning.

The Giza Plateau

Even though it’s two kilometers away, the Great Pyramid is the biggest thing on the horizon. It looms over the Giza Plateau, which in turn looms over the city of Giza. It’s hard to describe just how large the pyramid is; it’s more of a geographic feature than a building. And there’s this even bigger contrast between the Pyramid, which embodies the eternal, the ahistorical, and the enigmatic, and the city of Giza, which is painfully modern: McDonald’s, pirate DVD’s, internet cafe’s…

We took the bus through Giza. There were surprisingly few scammers of any kind - the tourists were keeping away because of the recent coup d’etat. I felt strangely anonymous - I’d expected children selling trinkets, “discount” tickets, old men with suspiciously cheap watches… but there was none of that.

Is this the world’s oldest megastructure, I wondered, a testament to the creativity and power of human civilization? Or is this the world’s oldest tourist trap: a dismal, decadent, Disneyland?

For Eason and me, it didn’t really matter. It’s important not to be too introspective when breaking the law. We weren’t approaching the Giza Plateau as tourists. We’d come with a specific goal in mind: sneak inside the plateau, wait until night time, and climb to the top of Khufu’s Great Pyramid.

As perpetually underprepared travelers, we needed to wander through Giza to find the supplies necessary for our ascent. Our quest for food, water, and cardboard gave us the opportunity to scope out the fence that separated the Giza Plateau from the city of Giza.

The fence was about ten meters high. The bottom half was concrete and the upper half chain-link topped with an extra dash of barbed-wire. The fence was adjacent to a slum, so we figured that there had to be some sort of hole drilled in it. However, after an hour of trudging through the slum, we came to the conclusion that the wall was impenetrable.

We began retracing our steps back towards the official entrance. This entrance is easily recognizable because of the presence of screaming children, guys selling Pharaoh hats, and overweight Americans embroiled in intensely whispered arguments - we’d finally found the last remains of Egypt’s tourist industry. It’s the same sort of crowd that you might see at an amusement park, soccer game, or a beach in Florida.

After we paid the entrance fee and wandered a little deeper into the plateau, the atmosphere changed completely. The pyramids are so huge that there’s no reason for crowds of people to coalesce. This was nothing like the Louvre, where tourists are jockeying to get a picture of themselves and the Mona Lisa. The pyramids belong equally to all guests: you can see them from anywhere.

The pyramids make you think about geometry - the angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees and all that. You’re reminded how creative and intelligent ancient people were. In the third century BC, the Egyptian Greek Eratosthenes set up an experiment that accurately determined the size of the Earth: two wells were identified, one in Alexandria and another in Syene, near the moden city of Aswan. By measuring the angle of light that was cast into these wells on the same day of the year, Eratosthenes was able to determine which percentage of the Earth’s circumference separated Alexandria from Syene. His conclusion, that the Earth’s circumference was 252,000 stadia, is within 2% of the correct value…

After a few hours of wandering through the sand, we eventually found a collection of tombs that made for a decent hiding place. One of the tombs was accessible: a yawning rectangular opening at the bottom of a depression in the sand, a maw shrouded in shadow. It was like something from an Indiana Jones movie, except that upon closer examination the tomb turned out to be filled with soda bottles instead of snakes.

We laid our cardboard pieces outside the entrance of the tomb and struck camp. The falafel balls and bottles of water we’d bought quickly vanished, as did the sun. Twilight, Eason argued, would be the best time to start our climb. He was right.

An Unlawful Ascent

The safest part of the Pyramid to climb is the South-West corner. An asphalt road runs along the pyramid near here, and across from it is the necropolis where our tomb-campsite was located. As we abandoned our camp and approached the pyramid, the tombs offered us concealment: by hugging the sandstone walls and walking slowly, it would be almost impossible for the guards to notice us. We made it to the edge of the road, still hidden by the tombs, and stopped to take account of the situation.

I was nervous. We would have to make it across the road, up the first blocks of the pyramid’s base, and all the way to the top and back without being caught by the guards or falling to our deaths. The blocks aren’t exactly stable: they’ve been battered by the elements for the past 4,500 years. The whole structure is slowly melting: transforming, poetically, I suppose, back into the sands from which it emerged.

But there was no time for poetic thought: there were no other people around, and it this was our chance. We had to take it. So we dashed across the road to the base of the pyramid and heaved ourselves on top of the first block.

Eason and I are tall (we’re both almost 200 cm, or 6’6”). I don’t know how anyone much shorter than us could reasonably heave themselves on top of one of those blocks. Luckily, as I’d learn soon, the blocks became shorter as the pyramid got taller, shrinking from maybe 170cm at the base to 130cm near the summit.

We scrambled up a few more blocks before lying on our stomachs to take a break. I crawled towards the edge of the block and looked down. On the road we’d just crossed was a car. It approached the corner we’d just dashed up. A pang of adrenaline shot through me. Two people exited the vehicle, both carrying flashlights. I thought we’d been busted already - night vision goggles, motion sensors, drones - I thought of all the ways we could have been detected. But the guards paid no special attention to the corner. They simply followed the road towards an outpost building a couple hundred meters away.

After a little while we decided to continue our ascent. Every few minutes take a rest, peer over the precipice. Most of these times we’d notice activity on the road below - more men with flashlights. But no matter how long the guards lingered near the base of the pyramid, they’d eventually depart.

Things were going well until about a third of the way up, when we were interrupted. As I was lurched over the corner of a block, my entire body was suddenly illuminated. Deer in the headlights, I was momentarily paralyzed. ‘Shit!’ I hissed at Eason, ‘They’ve got a spotlight on us!’

We lay prone and crept toward the edge of the block. There was a spotlight on us, but it wasn’t from the guards: there was a huge light system illuminating the entire southern face of the pyramid. It was the evening light show to entertain the tourists, something we would’ve known about if we’d opened any guidebook. We were caught in the middle of it.

If we started climbing again we’d certainly be caught. Although our bodies were tiny compared to the massive face of the pyramid, a well-trained eye would notice our shadows against the sandstone background.

But after a few minutes the lights were cut. We waited until we’d convinced ourselves that the light show was over for the evening, and then resumed our climb. After another few minutes the lights came on again, and we were forced to retreat into the shadows on the eastern side of the corner. Things were beginning to resemble a real-life version of the children’s game red-light green-light, but with possibly fatal consequences. When the lights were on, we froze. When they were off, we climbed as quickly as possible.

As we got closer to the pyramid’s apex, I could feel the cold desert air on my skin. When I turned my head, I could see faint urban lights on the ground below. But I absolutely refused to look down, even to speak to Eason, who was a few blocks below me. I couldn’t make myself look down to speak to him: we would only talk only during breaks while resting on the same block.

The pyramid rises at an angle of about 45 degrees. 45 degrees doesn’t seem that steep if you look at it on a protractor. But when you’re hugging the side of a pyramid, that’s an angle steep enough to make the horizon vanish below you, creating the illusion of a perpetual vertical drop.

I guess the adrenaline let me fight through the fear: I was never paralyzed like I usually am by heights. After about thirty minutes we were almost there. I could see the last few blocks above me. But then things got tricky. Up here, the blocks started disintegrating. Although terrifying near the base, there wasn’t much of a risk of slipping and falling. Up here the conditions were much worse: the cracked and slanting rocks made it more challenging to find a stable foothold. Our pace slowed.

We were both getting numb. Our hands were sore from the wind and from scraping against the rocks. But we made it. I heaved myself over the last block and crawled towards the center of the pyramid’s flat top. Eason was a few seconds behind me, rising to his feet and making a more dignified victory procession.

As I admired the new bruises that were forming on my arms, hands, and legs, I also had the chance to admire the graffiti: the pyramid was covered with it, carved into every surface. Names that looked Italian, French, Greek… Phrases chizzled in scripts I couldn’t identify… Lots of little gashes that were Arabic… Scribbles that were indecipherable, maybe first names or professions of love or victory or erotic poems. I don’t know how many generations of people had left their mark up there, but I decided to take out a pen and leave a mark of my own.

We paced back and forth. The city of Giza was a constellation spread across the Earth. We sucked up the illumination of the city below us. We were breathing it like air. The warmth was being sucked out of us by the gnawing desert cold. Climbing above Giza, rising above the tourist crowds, we’d discovered the real history of the place: it was etched across the sandstone blocks by generations of rule-breakers like ourselves.

We made our descent. Nobody spotted us on the way down, or as we crossed the road, or even as we walked along the road towards the entrance. Some of the guards gave us strange looks as we exited the plateau. They smiled when we greeted them with ‘salaam alaikum.’

On the walk back Eason pulled out his phone and bought tickets to Athens. The plane was departing in six hours. It was just enough time for us to retrieve our bags and be off.

Train to Macedonia

A few days later I was suffering from a head cold in Thessaloniki, a large city north of Athens. We were thinking about sneaking into Mt Athos, a special religious enclave carved out of Greece that’s three times the size of San Francisco; home to a string of Orthodox monasteries - no non-believers allowed, and no women. But I was feeling too sick. So instead we got on a train heading towards Macedonia. A man entered our cabin and pulled out a bottle of vodka which he insisted we share. America, I love America! he repeated after every sip.

When he learned that we’d come from Egypt he told us that the Rosetta Stone was written in three languages: Egyptian, demotic, and Macedonian, “a Slavic language” he asserted with a smile. Macedonians, we’d soon learn, were very proud of their history, even if a lot of it was made-up: Alexander the Great was a Macedonian Greek, not a Slav - the latter group borrowed the name but are later arrivals in the region. And as for the Rosetta Stone, it’s only written in two languages: Ancient Egyptian and Ancient Greek, although the former is repeated in two different scripts: hieroglyphic and demotic.

As I started arguing with my new friend about the linguistics of the Rosetta Stone, the liquor hit me in a warm wave, and I realized I never saw the sphinx. We’d skipped it entirely in our rush to find a hiding place. I’d never gotten to see the mysterious face - probably Khafre’s, who was buried in the second-tallest Giza pyramid - the face with the curiously vacant stare, like the Mona Lisa, the face that watches over aeons. I never had a chance to look at the Dream Stele, which rests between the Sphinx’s paws. This stele recounts the story of Thutmose who is promised the White Crown, the Red Crown, and soverignty over Egypt… if only he clears the sand that’s covering the mighty body of the Sphinx. And like Thutmose’s dream, I feel the warm sand covering my body, and drift off to sleep…