Hitchhiking Kurdistan 🚗

In 2016 I hitchhiked from Sulaymaniyah in Iraqi Kurdistan to the ancient town of Hasankeyf in Turkey (map). Hasankeyf now rests on the bottom of a lake - submerged in 2020 after the completion of the Ilısu dam. When I first jotted down the notes that would become this story I never imagined that the ancient valley full of austere minarets, Turkman bridges, crumbling caravanserai’s, and stone houses stacked one on top of another would be wiped from the face of the earth.

Kurdistan is an ancient place. Hasankeyf wasn’t the greatest city to be lost to time, only the most recent. The forces of migration, economics, and conquest have have added layer upon layer to this region of the world - one layer crushing down the next, imperfectly erasing it, again and again. In 2016, Kurdistan was at war again:

](/assets/images/2021-02-21-hitchhiking-kurdistan/peshmerga_vs_isis_15s.gif)

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or ISIS) was born in the deserts of Western Iraq, where fighters driving technicals overran cities and proclaimed a new islamic caliphate. ISIS militants massacred Shia’s, Yazidi’s, and any Sunni Muslims they viewed as heretics. The Islamic State quickly metastisized, following the path of the Euphrates all the way to the gates of Baghdad in the East while also threatening Damascus in the West. This part of the world had been torn apart by the Syrian and Iraqi civil wars - cities depopulated, factories abandoned, the desert reclaiming farms, sand washing over highways… This region had barely begun to recover before being overwhelmed by a new enemy.

In the East, Syrian forces with Russian military support managed to keep ISIS away from the densely populated Mediterranean coast even as it gobbled up a third of the nation. In the North, the world watched as Kurdish forces in Rojava repelled the Islamic State during a protracted siege - the Stalingrad of the Syrian Civil War - even though later the Turks would betray their erstwhile allies as the city was bargained off to Assad and Putin. Out of the chaos a new proto-state, Rojava, would be born - an experiment in libertarian socialism in the Kurdish heartland.

While this was happening in the North and East, the Islamic State was fighting American and Iraqi forces on the outskirts of Baghdad. The tide was beginning to turn in favor of the Kurds: the Kurdish security forces (Peshmerga) were launching a campaign to liberate Kirkuk - sometimes called “the heart of Kurdistan” - from ISIS. The TV stations had 24-hour coverage of the fight: Peshmerga soldiers rushing to the front lines, machine gun fire kicking up clouds of dust, shaky images of mortar shells obliterating neighborhoods, the bodies of heroic Kurdish martyrs being pulled from the rubble…

I decided that I needed to revisit these old notes in order to take account of everything I experienced in this chaotic part of the world. Without some kind of narrative these memories are just disconnected fragments that can whither away and melt like an ice cube in the desert heat. The war is the backdrop, the setting, and I was lucky enough to only experience it indirectly - but I’m still entangled. This article recounts my experience hitchhiking across northern Iraq in 2016 and can act as a guide for anyone else who wants to explore this ancient and interesting part of the world.

Where I enter the story is at Sulaymaniyeh International Airport in Iraqi Kurdistan…

Slemani

Sulaymaniyeh (السليمانية - reduced to Slemani by the locals) is one of the largest cities in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq. Americans need a visa to enter Iraq, but not Kurdistan - a nation inside a nation. Americans are viewed positively here - after all, it was George W Bush who killed Saddam, a great enemy of the Kurds, and whose father, George H W Bush, is credited with protecting the Kurds during the first Gulf War by establishing a no-fly zone. America, great! the border security official said as he did a cursory inspection of our passports and stamped them.

Outside the airport, I immediately noticed the overwhelming smell of diesel - with a power grid prone to failure and sabotage, many homes and businesses run their own generators, powered by petrol that’s only slightly more expensive than bottled water. A brownish smog hung over valley, blending in with the hills on the horizon. As we walked from the airport towards the city center, a driver was kind enough to pull over and give us our first ride.

We found a hotel and dropped off our bags before setting out to explore. The city was beautiful, complicated. Small parks and gardens overflowed with pomegranates and daffodils. Ancient mosques were sandwiched between new mid-rise apartment buildings. Armed convoys patrolled the streets, men with guns walking right past revolutionary graffiti - PKK Peshmerga Öcalan.

There’s a hill in the middle of the city that overlooks everything - sort of like the acropolis in Athens. Perched on top is the Grand Millennium Hotel and shopping mall which we visited to get a view of the valley. The building was mostly abandoned - just a skeleton crew of guards and cleaners to keep the place from being robbed or falling into decay. This weird kind of abandonment - upscale infrastructure build for an upper class that doesn’t yet exist - would be repeated in different forms in other places in Iraq.

From the Grand Millennium we descended into the old city, where the grid yields to a chaotic tangle of ancient streets and alleyways. The market (souq in Arabic, borrowed into Kurdish) was packed with activity of every kind: street vendors selling watches, kids chasing soccer balls, old arch-backed men under umbrellas playing cards or smoking hookahs.

The lack of women on the streets was very obvious: it was men playing snooker, men buying toilet paper, men baking bread, men strumming guitars, and men shooting friendly smiles and greetings at us. Many of the older men wore the traditional Kurdish outfit: baggy Aladdin pants, a shirt of the same color, a sash around the waist so that it looks like the outfit is one piece (not two), a vest, a keffiyah tied around their head, and a blue or white undershirt - an outfit that looks stifling, but is perfectly designed for the dry sunny desert.

These bakers were enthusiastic about getting their picture taken. Unlike conventional travel destinations, there are no signs of scammers or criminals anywhere in Kurdistan - all the friendliness we experienced was genuine, though it took a few days for me to lower my defenses and learn to accept the local hospitality.

After a couple days exploring Slemani we decided to hit the road. We walked to the edge of the city where the valley fanned out into a dusty plain. In the shade of a tall olive tree we dropped our bags, stuck out our thumbs, and got into a car heading West.

The Tomb of Cyaxares

Kirkuk is a mostly straight shot West from Slemani - the highway meanders over some ridges and mountain passes, but it takes less than two hours to make the 70 mile drive. It was important that we stay far away from Kirkuk, an ISIS stronghold which was under siege by Peshmerga fighters. The driver let us out at Tasluja, where the highway forks north towards Dokan, leaving a wide margin between us and the fighting.

In a convenience store in Tasluja I stared at a TV resting atop a tower of strawberry wafer boxes. On the screen were images of the fighting. Convoys of soldiers took cover behind dirt berms as bullets whizzed overhead. Someone’s body was lying supine in the middle of a dusty street, slain by a sniper. A shell-shocked soldier was being interview by a TV crew, barely able to string words together, his hair disheveled, the interviewer interpolated patriotic sayings on his behalf. The cashier struggled to peel his eyes away from the screen as he rung me up. We both stared silently at the screen like zombies for several minutes after I’d made my purchase, transfixed by scenes of chaos that were unfolding just a few miles away.

We jumped in another car and headed North. Halfway between Tasluja and Dokan is the tomb of the Median King Cyaxares in a place called Qyzqapan. Cyaxares’ forces clashed with the Lydians in the battle of Halys. During the battle, an eclipse occurred, turning day into night. Interpreting this as an omen, both sides agreed to stop the bloodshed. Because it occurred during The Eclipse of Thales, this battle is the oldest historical event that is known to the exact day (May 28th, 585 BC). If only coincidences of nature could prevent confligt in modern times as well…

The tomb itself is half-way up a sheer cliff face, which makes you wonder how it was ever carved in the first place — though the metal scaffolding that lets you climb up to it suggests that an ancient wooden scaffolding once existed here. From the top of the raised platform you can see miles and miles of rolling brown hills, the faded scars of dirt roads, and a few flocks of sheep being chased by their shepherds.

The tomb is flanked by primitive-looking Ionian columns, which predate any Ionian Columns in Greece - this has led some historians to conclude that this architectural style was invented first by the Medians. Also, in contrast to its standard depiction, the Faravahar symbol left of the tomb’s entrance has wings that curl upwards. I’m not sure why someone spray-painted ناتۆ (NATO) all over the tomb’s facade.

The road to Qyzqapan is narrow and almost completely untraveled. We were lucky enough to get a ride almost all the way there, and only had to walk about a half hour. We were equally lucky on the way back, when Hiwa, a Kurdish man from the UK who was home visiting family, gave us a ride. He took us to see some of the local tourist attractions: a lush valley packed with shrines, a panoramic pull-out on the side of the highway, and some stops to visit cousins. He insisted that we have lunch at his home.

We were driven into a remote hamlet deep in the hills and chauffeured through trellises draped in grape vines. At the fammily home we met Hiwa’s father, who sat crossed-legged next to us on the floor and joined us for tea as the meal was prepared.

A plastic sheet was spread out on the carpet, then dishes overflowing with rice, tomatoes, peppers, green onions, kebabs, cucumbers, feta cheese, olives, flatbread, clear soup, and yogurt. My favorite Kurdish food — yaprax (vegetarian cabbage wraps that resemble dolmas) — were part of the spread, and the family found it funny that I was able to devour so many.

After a couple of hours enjoying a Kurdish lunch, Hiwa whisked us back to the highway where we caught another car heading towards Dokan and Erbil. At some point I stopped and ran down to the Little Zab river and put my feet in the water. This river flows south east and empties into the Tigris, marking the halfway point between Kirkuk and Erbil.

The Peacock Angel

Erbil is to Slemani as New York is to San Francisco: buildings that are bigger, taller, denser - an atmosphere that’s more authoritarian, traditional, and chaotic, but also more diverse, faster paced, bigger. On the drive into Erbil I remember speeding past rows and rows of soldiers flanking the highway, standing rigidly in formation, rifles over their soldiers, facing the traffic. I remember the armored personnel carriers parked at intersections, soldiers camped out in the shade created by tarps draped over tank cannons. Downtown there were men in suits everywhere, scurrying between their cramped and sweaty apartments and office buildings, mingling with soldiers and the merchants, thick and diverse crowds.

Eason and I were a curiosity here. We’re both 6’6” (almost 200 cm), thin, and dress strangely (especially by Middle Eastern standards). Many people wanted to chat with us. We got a lot of stares. Like in Slemani, the locals were genuine and friendly - no hint of crime, scams, or any anti-American sentiment.

My notes from Erbil are sparse. They’re eclipsed by what I saw later on. A few hours northwest of the city is Lalish, a temple complex that’s the holiest place in the Yazidi religion. We wanted to visit, but again we had to take a long detour to avoid another city occupied by ISIS forces: Mosul, a place that saw fierce fighting in 2004 during the American invasion and had fallen to ISIS in 2014.

We hitchhiked the backroads, crossing the Great Zab River where I took another dip and snapped some photos. The austere terrain was mostly empty - just a few small hamlets scattered here and there in ancient dried up valleys. At many of the rest stops I’d see large propaganda posters of President Barzani and flags from his Kurdistan Democratic Party.

It was getting dark so we decided to overshoot Lalish and spend the night in Duhok, a medium-sized city flooded with Christian and Yazidi refugees who had fled the onslaught of the Islamic State. As non-Muslims, these groups were vulnerable to persecution by ISIS - especially Yazidis, who aren’t people of the book (followers of Abrahamic religions who are fellow monotheists) and are frequently referred to as “devil worshippers” by their neighbors. This is possibly the result of an unfortunate linguistic coincidence: a dubious connection between the pronunciation of the Yezidi deity Tawsi Melek and shaitan (satan).

The next morning we decided to cheat and hire a taxi to drive us to Lalish. We weren’t sure what reception we’d have and wanted the legitimacy of a paid-ride. Our driver, a Muslim, was nervous about the prospect of bringing us into a den of devil-worshippers, but reluctantly agreed. Eventually he became as enthusiastic about the road trip as we were.

On the way to Lalish I saw a column of black smoke pouring up from the horizon. As we approached I noticed the smoke stack of a huge oil refinery. Not long after that the car broke down. Eason and our driver spent a half an hour replacing the gas pump. Our driver brought us into the narrow meandering valley of Lalish and dropped us off in a mostly empty parking lot. He told us he’d come back and pick us up in a couple hours.

Yazidis believe that god created the world by casting a white pearl into the cosmic ocean. As it sunk into the depths, the pearl shattered, becoming the substance from which the material universe would be formed. To assist in his work, god created the Peacock Angel, Tawsi Melek. Six more angels were fashioned by god to assist Tawsi Melek, greatest of the angels, in his creation of the world.

After the earth was created it began shaking uncontrollably. Tawsi Melek descended from heaven in the form of a peacock and stopped the shaking. He then transferred the rainbow colors of his plumage to the earth, filling it with flora and fauna. The place that Tawsi Melek descended is Lalish.

Many of the religion’s holiest places are located in this city. The centerpiece is the tomb of Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir, but there are many other smaller sites and ruins. The tomb had a large courtyard in front of it where a few people were milling around. A couple of old men dressed in white robes sat near the tomb’s entrance, their eyes closed, in some kind of meditation. The place was quiet, but not uninviting.

To the right of the tomb’s arched entrance is a large black snake cast out of metal. According to legend, this might have once been a living snake that had attacked the residents of Lalish, being turned into its harmless metallic form by the power of Sheikh Musafir. According to a different legent, the snake might also be the physical manifestation of one of the seven angels that serve Tawsi Melek.

I was fascinated by the proliferation of weird and abstract animal shapes carved into rocks scattered around Lalish. I asked the locals about the meanings of the symbols. While some have obvious meanings, others were more mysterious.

After spending half a day in Lalish, we drove back to Duhok, gave our driver a big tip (we’d be in Turkey soon where our Iraqi dinars would be worthless), and collapsed from exhaustion.

Duhok to Mor Gabriel

We set out for Turkey the next morning. A curtain of dust danced on the peripheries of the highway. I visualized a giant mouth exhaling smoke, sucking us in. Roadblocks were more common here. When we passed one, the local militias would ask us to step out while they investigated. Walkie talkie communication. Usually they had no idea what to make of us — two tall, thin, beardless Americans — software engineers from San Francisco — obviously not part of ISIS — not spies — but tourists? — No way.

We were invited into one of the guard stations where we were given tea and biscuits. The militiaman proudly pointed to a picture of George Bush on the wall behind him. We had to wait until each of his comrades took turns gawking at us and experimenting with different English phrases: Where are you from? America, good! Do you like Kurdistan? I love you.

I’d managed to learn a little bit of Kurdish myself. Unfortunately, I’d studied Sorani Kurdish, which isn’t spoken in the northern part of Iraqi Kurdistan where Kurmanji is dominant. The Kurdish languages are as diverse as the Romance languages: Sorani, Kurmanji, Zaza, and Gorani are like Spanish, French, Italian, and Portuguese. Despite my language limitations, the militiamen were extremely excited that I knew a few words in Kurdish - even if it was a dialect they didn’t speak

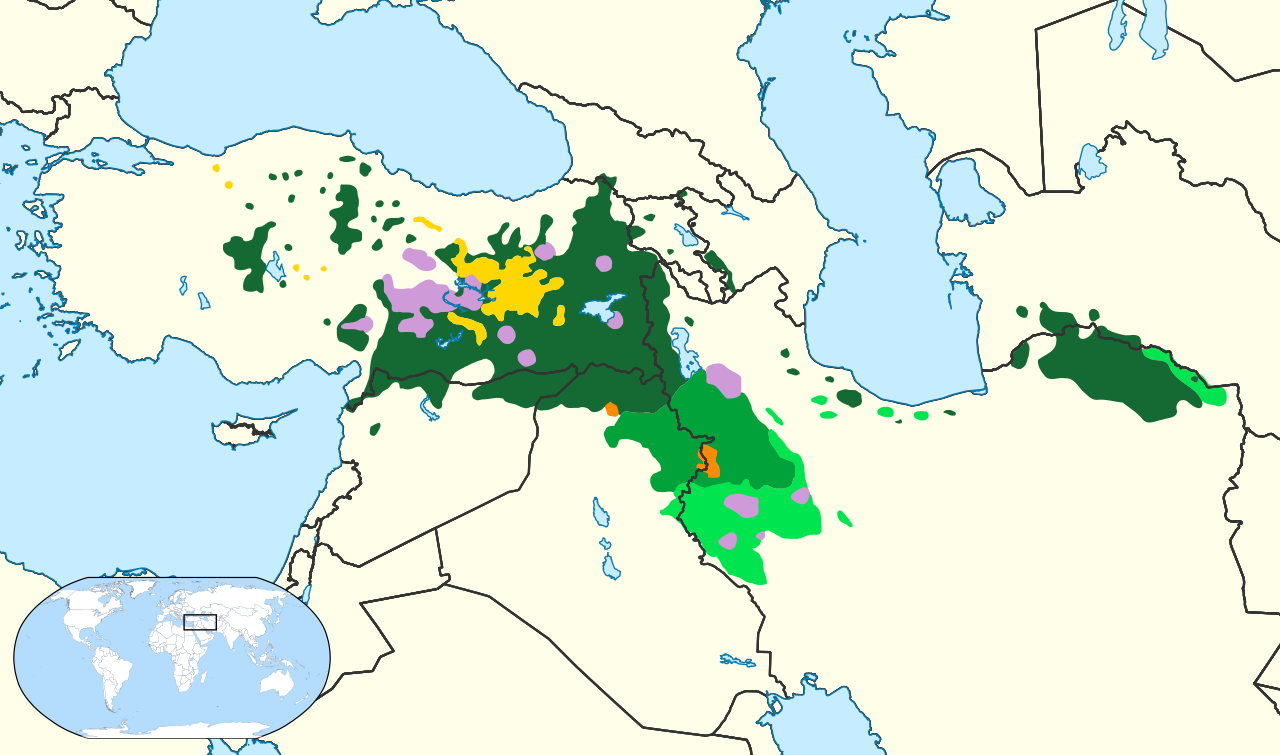

In the same way that the Kurdish people are divided into different language groups (map, below), they’re also divided between four different countries: Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran. The Kurds are the largest ethnic group in the world without their own country. We’d be passing from Iraqi Kurdistan into Turkish Kurdistan, scraping right past Syrian Kurdistan (Rojava).

Zakho was our last stop before Turkey. Sketchy like every border town is sketchy. Very bad vibes. We collected conflicting sources of information about the border — we might have to walk across… or maybe take a taxi… then we should register with the militia before leaving — no, after we reach the Turkish side… hitchhiking will be OK… hitchhiking will get us arrested. Whatever.

Somehow we made it to Turkey. We passed through Silopi: truly hellish. A thin veil of smog hung over the city. The highway had large gravely margins where truckers had pulled off the road to smoke cigarettes, eat kebabs, drink tea. A man materialized out of the haze and offered us a ride.

Just before Cizre the highway arched towards the Tigris. Just a few meters away was the river. Right across it Rojava. A new country going through its birthing pains. A place where other Westerners had gone to fight, tried to manifest their utopian visions, died. I understand this fantasy: the limitless potential of chaos, the undressing of civilization, shaking the etch-a-sketch. I felt the pull.

We arrived late at night in Cizre. I remember dusty plastic fruits hanging from the balustrade of our cheap hotel. There was a two-inch gap beneath our room’s door that let flies pour in.

The next day we took the D380 highway west. We stopped at Yayvantepe where a wealthy tourist couple drove us the 2 miles from the highway to Mor Gabriel, the oldest Syriac Orthodox monastery in the world. They laughed and joked with us. The man had wrap-around sunglasses and drove with one arm dangling out the window. His partner had dyed-blonde hair and the shortest skirt I’d seen in weeks.

We explored the monastery, snapping pictures of the fortifications, catacombs, and the expansive view of the encircling landscape. There were a few other visitors milling about, all Turkish, and at some point our foreignness became obvious to the monastery’s staff. A man invited us to a small private waiting room where he summoned a boy to serve us tea. The walls were covered with framed photographs of Syriac artifacts, calligraphy, and monks. We sat in stiff-backed wooden chairs and talked about Syriac Christian culture and the strained relationship between the Assyrians and their Turkish neighbors.

The man was the secretary of Mor Timotheos Samuel Aktas, archbishop of the Tur Abdin diocese. After an enthusiastic exposition of the Syriac alphabet and its origins in ancient Phoenicia, we were introduced to the archbishop himself — on the spectrum from holy man to wizard, we was firmly on the wizard side.

We walked most of the way down to the highway. The road sunk into a thick pine forest. Birds darted back and forth between branches. A driver picked us up and took us north.

Hasankeyf and Home

This is where my notes start to fail. If you’re reading a historical text — something Greek, Babylonian — you’ll encounter these gaps called lacunae where the text has been damaged. Sometimes these lacunae get filled in when another copy of the text is found, but just as often the holes are so large that translators have to guess — or leave the guessing up to the reader.

At some point we were picked up by a van full of young men. They joked around and offered us cigarettes and alcohol, which we refused. The driver slammed the gas pedal to swerve between cars and trucks, barking out laughs and screams, flicking cigarettes onto the asphalt. He turned fully around, one hand still gripping the steering wheel, foot flat on the gas pedal, to slap me on the arm and say “America, great!” He approached a small pickup truck, tailgating it closely and cursing under his breath. On a sharp curve he decided to overtake the car, swerving into the opposite lane before darting back in front of it.

At some point one of the guys in the back told us that they were members of the Gray Wolves. They showed off their uniforms and suggested that there might be firearms in the trunk. They demonstrated their organization’s salute — a hand gesture that resembles the “silent coyote” American kids learn in Elementary School.

The Gray Wolves are a Neo-Fascist paramilitary group, part of the Turkish “deep state” that’s responsible for systematically oppressing and murdering Armenians, Greeks, Kurds, and non-Muslims. In 1978, Gray Wolf militants massacred almost 200 Alevi Kurds in the city of Kahramanmaraş. During the war between the Kurdish PKK and the Turkey, the Gray Wolves have been the main instrument of Turkish state violence: responsible for the torture, murder, and forced disappearances of civilians across Kurdistan.

There are lots of far-right groups in the world — even more after the election of Trump — but few of them approach actual fascism. The Gray Wolves, however, easily qualify: A Turkish-supremacist ideology, a willingness to murder ethnic minorities, a disdain for liberalism and democracy, and an enthusiasm for genocide…

The Grey Wolves I met didn’t seem like terrible people at first, but, you know, they were… They dropped us off in Hasankeyf.

I can’t remember approaching the valley because I never knew that it would be something worth appreciating. But I remember the little cafes scattered along the river. The bridges crossing it, some standing strong and others in ruins. There were small buildings honeycombed on a giant pillar of rock, a tower perched on top of it. Minarets poked out of the town, a mixture of ancient and contemporary construction.

In 2018, the Turkish air force destroyed Ain Dara, a historical site with many similarities to Solomon’s Temple — possibly its inspiration, or its antecedent. Unfortunately, this wouldn’t be the last historical site destroyed by the Turkish state. In an attempt to “modernize” Kurdistan, Hasankeyf would have to be sacrificed: submerged by a new hydroelectric project.

I can’t help thinking that my ride with the Gray Wolves was some kind of prelude to the disaster that would overtake the valley: such an obvious statement of invasion and occupation. But in this part of the world, conquest is cliché — the Turks first invaded Anatolia a thousand years ago, using horse archery tactics learned from the Huns to crush the decaying Byzantine Empire. Before them it was the Arabs, the Greeks, the Persians, the Hittites… Eventually European powers swept over the land - unseating the Ottoman rulers, then the Americans bumbled onto the scene, destroying civil institutions that would directly lead to the rise of ISIS…

The past really weighs down on me sometimes. I can see the outlines of these huge historical forces, the marks they leave on the Earth, the ruins, and I think of my place in all this chaos. I wonder if it’s meaningless — there will be some new invaders, some new victims, and the cycle will go on. Or maybe the utopians are right — you can wipe the slate clean and have a fresh beginning, grind the temples to dust and build them back up. I don’t know the answer. But I’m glad I mixed myself up in Kurdistan instead of letting the sand pass through my fingers.